Requiring Provenance: An Injustice to Ancient Coin Collectors

By: Alfredo De La Fe

At the 2015 Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) hearing to discuss a potential renewal of the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Italy, Prof. Patty Gerstenblith, Chair of CPAC, cited text from a Numismatica Ars Classica catalog stating that the firm will provide documentation for coins subject to US import restrictions. She asked if NAC can provide such documentation why can’t other firms? Of Course, NAC cannot provide provenance for all the coins in its sales and the documentation cited would undoubtedly be some form of certification by personal knowledge or belief.

In my experience, less than one coin in a thousand has retained its provenance/pedigree information over the past five centuries of active coin collecting. Simply put, this information rarely exists. In the antiquities trade, these items are considered “orphaned artifacts”. Many common or low value coins were sold without provenance information and typically were not photographed for the sale catalogs—If there even was a catalog or public record. The vast majority of coins sold in private transactions were not photographed. Photography did not even exist until the mid 19th century and did not become common in the numismatic trade until the later 20th century. Thanks in large part to the advent of the internet and the use of online stores and internet based auctions, that situation is changing.

When attempting to research a “lost pedigree”, one quickly discovers that many coins have been cleaned or conserved throughout the years, making it more difficult to easily identify a coin from an earlier photograph or plaster cast. Occasionally a dealer will get “lucky” and stumble upon a coin’s pedigree when researching a specific coin–especially if it is rare or unusual. But more often than not, once a coin has lost its provenance the information is lost forever. There have been several notable examples over the past thirty years where dealers have gotten “lucky”.

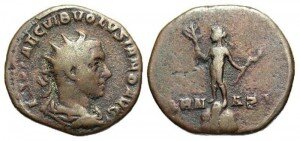

In the Agora Auctions Electronic Sale #31 of Ancient and Medieval coins closing on April 28th 2015, is an apparently unique Roman medallion of the emperor Volusian, that has a very old pedigree! What is of particular interest is that this coin had been “missing” since ca. 1830 and had lost all of its provenance information.

Medallion of Volusian

Lost it's pedigree going back to the 18th Century

The coin, formerly residing in the Wiczay collection, was first published by Eckhel in 1775, and subsequently cited in Cohen. Purchased after Wiczay’s death ca. 1830 by the Parisian coin dealer Rollin, it had been missing until its recent chance discovery at a coin show in the United States.

In an online discussion concerning this coin, Curtis Clay wrote:

“JUDGING FROM ECKHEL’S DRAWING, THE WICZAY SPECIMEN, LIKE [AGORA’S], HAD A LITTLE EXTRA METAL OUTSIDE THE BORDER OF DOTS AT THE LEFT ON THE OBVERSE, AND HAD TWO SMALL INDENTATIONS ON ITS UPPER EDGE ON THE REVERSE, AT A LITTLE BEFORE 12 O’CLOCK AND A LITTLE AFTER 1 O’CLOCK RESPECTIVELY.”

I think these correspondences can hardly be coincidental, so do not doubt that [Agora’s] coin and Wiczay’s represent one and the same original! …” If not for the eagle eye of a highly-acclaimed numismatist, this coin probably would never have been identified as the coin cited in Cohen!

In 2014, a Celtic silver tetradrachm was submitted for identification and grading to Numismatic Guarantee Corp (NGC). The coin had ‘cabinet toning’ suggesting that it had been apart of an old collection. While researching this coin in the standard reference for the series it was discovered that an image of this very coin was in the publication! [The Coinage of Damastion and the Lesser Coinages of the Illyro-Paeonian Region by J. M. F. May, published in 1939 at the Oxford University Press. Plate 8, coin 100a.] You can read more about this interesting discovery here.

In 2012, authorities of the British Museum joined other major museums in establishing a policy of not exhibiting artifacts and ancient coins that did not have a provenance/pedigree dating to 1970 or earlier. Consequently, the museum informed a collector who had loaned a spectacular sestertius of Hadrian that the coin could no longer be displayed because its recorded provenance only want back as far as 1980. A year later negotiations began to display this coin at another prestigious museum. Once again, the provenance issue came up. However this time, while looking through an earlier auction catalog in the Nomos Library at Zurich, It was discovered that the coin had a lost provenance dating back at least to the mid-19th century! Remarkably, a photograph of the coin in the sale catalogue of 1906 showed that the coin was at that time uncleaned. Clearly, it had since been professionally conserved. CoinWeek published the details, you can read it here.

(See also: The Celator, “Pedigrees and Price” by Dr. Alan Walker”, where many additional examples are cited.)

A small but influential group of archaeologists have publicly taken the stand that any trade in cultural property is unethical. Their ideological view has found support within several agencies of government, where the repression of international trade in coins and artifacts is becoming a major initiative. Customs, following the lead of the U.S. State Department, has shifted the burden of proof from the government to the importer in cases of MOU designated list detentions and seizures. They have essentially taken the position that all coins are illicit unless proven otherwise. Importers are subject to being treated as looters or those that support and encourage looting by the simple act of importing a coin that was legally purchased in international trade.

In an ideal world it would be fantastic to have provenance information for every object from antiquity. Unfortunately, ancient and medieval coins have not carried this information as they have changed ownership. Even important coins have often lost their provenance. A very small percentage of the millions of coins sold during the past five centuries have this information and, when they do have it, it is a rare occurrence. It is an injustice that provenance has become a requirement for importation of many coin types into the United States when no other country on earth imposes similar broad import restrictions. In any case, provenance may be more valuable in the years to come than it has been in the past.

Any legal requirement of provenance should be weighed against the fact that while there have been hundreds of thousands of collectors a very small percentage are currently active. Getting word out concerning such a requirement is an impossible task. What happens when 10 years from now a collector dies and his grandchildren find his old coin collection in the attic with no provenance? How will these coins be “grandfathered” in to the new requirement? Even if the “1970 standard” is relaxed and collectors are given a very long time to somehow register their collections via a third party service or photography, this would ultimately turn the greater majority of ancient coins which are already in private hands “illicit”.